Ancient Egyptian words reveal nowhere near just communication methods. They provide glimpses into a sophisticated belief system that revolved around life, death, and immortality. These terms went beyond ordinary vocabulary and represented complex spiritual concepts that guided civilization for thousands of years.

The ancient Egyptians developed profound ideas about existence through terms like “Ka” (the life force requiring the mummified body for survival) and “Ba” (the personality depicted as a human-headed bird). These concepts are the foundations of Egyptian religious thought. Their burial practices included specialized terms such as “Canopic jars” (containers for preserved internal organs) and “Shabti” (funerary statuettes that performed labor for the deceased). The ancient Egyptians really prepared for the afterlife. The “Book of the Dead” served as more than text – it contained 200 spells and rituals that guided souls through the underworld.

This piece uncovers the hidden meanings behind Egyptian words that shaped one of history’s most enduring civilizations. Many history textbooks overlook these significant terms and their deeper cultural impact.

The Soul in Ancient Egypt: More Than Just a Spirit

The ancient Egyptians stood out from other ancient civilizations by developing a sophisticated multi-layered concept of the soul. They believed the soul wasn’t just one thing but a complex mix of different spiritual elements. Each element had its own role and features. These elements show up as fundamental ancient egypt words that built their beliefs about the afterlife.

Ka: The life force that needed food

The Ka stood for the vital essence that marked the difference between life and death. Ancient egyptian terms tell us the Ka came to life when either the fertility goddess Heqet or the goddess of childbirth Meskhenet breathed it into a newborn’s body. This life force stayed with people through their lives and lasted after death.

The ancient Egyptians had a fascinating belief about the Ka needing food even after death. People left food and drink for the dead person’s body. The Ka took in these offerings through supernatural means instead of eating them. The Middle Kingdom Egyptians came up with special offering trays called “soul houses” to make this feeding process easier.

Ba: The personality that could travel

The Ba, another key part in egyptian vocabulary, matches what we think of as a soul today. People saw it as a bird with a human head. The Ba was someone’s unique personality and character. This part of the soul could move freely between our world and the spirit world.

The Ba stayed connected to the body during life but broke free after death. Ancient egyptian texts say the Ba could float above the dead body, meet with gods in the afterlife, or go back to places the person loved while alive. The Coffin Texts describe how the Ba could leave the body when someone died and eat and drink on its own.

Akh: The transformed spirit in the afterlife

The Akh was the immortal, changed self—a magical blend of the Ba and Ka that happened after death. Egyptian terms say this change could only happen with proper funeral rites. Spell 474 of the Pyramid Texts puts it clearly: “the akh belongs to heaven, the corpse to earth,” showing how the Akh surpassed physical life.

A successful transformation let the Akh live among the stars with the gods, though it could return to the body when needed. People could pray to their ancestors’ akh for help, but these spirits could also punish them if not kept happy.

Duat: The underworld journey

The dead person’s spirit had to direct itself through the Duat—the Egyptian underworld—before reaching the afterlife. This long and dangerous path had many challenges the soul needed to beat. The dead traveled both as themselves and as the Ba during this passage.

The biggest test waited at the end: weighing the heart against Ma’at’s feather, the goddess of truth and justice. Osiris welcomed those who passed this judgment to live forever in the Field of Reeds. Those who failed met a terrible end—Ammit ate their hearts, which stopped their existence completely.

Opening of the Mouth: Giving senses to the dead

The Opening of the Mouth ceremony was the most vital ritual in ancient Egyptian funeral practices. This detailed process on the mummy aimed to bring back the dead person’s senses. They could see, speak, hear, breathe, and receive offerings in the afterlife.

Priests used special tools like the adze and peseshkef to touch the dead person’s eyes and mouth while saying specific spells. They cleaned the body with natron (the salt used in mummification) and then covered it with perfumes and oils.

This ceremony changed the dead into an akh, bringing them back as an effective spirit. The soul couldn’t work properly in the afterlife without this vital ritual, which created a bridge between life on Earth and eternal life.

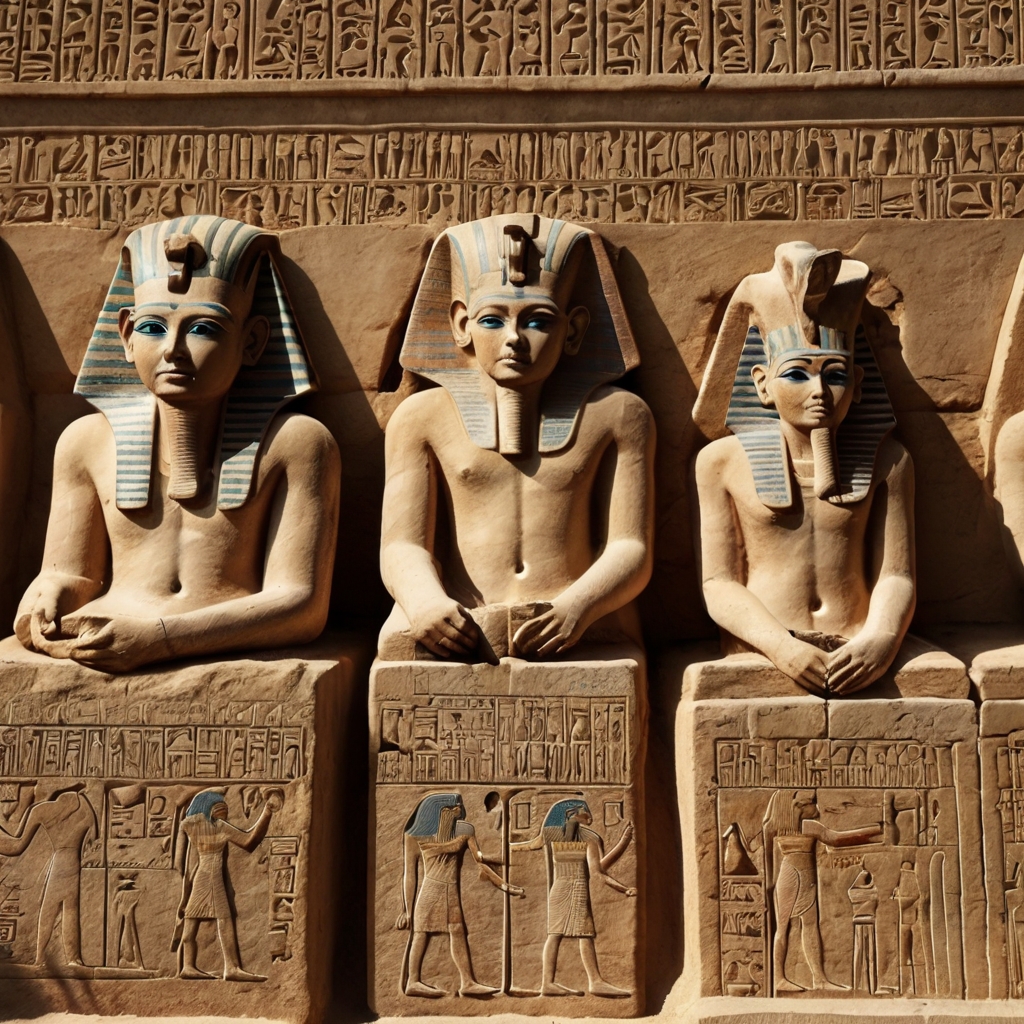

Symbols That Spoke Volumes

Visual symbols held immense power in Egyptian culture, beyond spoken and written ancient egypt words. These hieroglyphic elements served as channels of spiritual energy, protection, and core spiritual concepts that shaped both earthly life and the afterlife.

Ankh: The symbol of life

The Ankh, which looks like a cross with a loop at the top, represents one of the most recognizable ancient egyptian terms for eternal life. This powerful symbol dates back to the Early Dynastic Period (c. 3150-2613 BCE). The Old Kingdom people knew it as “Neb-Ankh,” which symbolized eternal life.

Gods often held the Ankh to the pharaoh’s nose to offer the “breath of life” symbolically. This egyptian vocabulary term symbolized the life-giving powers of air and water. The Ankh symbolized the union between male and female energies, heaven and earth, and shared a close connection with “The Knot of Isis”.

Coptic Christians later made the Ankh their own symbol (crux ansata), which shows its lasting impact across cultures.

Djed: The pillar of stability

The Djed pillar, known as “The Backbone of Osiris,” symbolized stability and permanence in ancient egypt terminology. This symbol shows a vertical shaft with four horizontal bars near the top.

The myth of Osiris gave birth to the Djed pillar. After Seth murdered Osiris, his backbone transformed into this pillar. Ancient Egyptians believed the Djed’s four pillars supported the earth’s corners.

This egyptian terms symbol played many roles: it represented the human backbone, helped the soul rise from the body toward the afterlife, and symbolized the gods’ lasting presence. People placed it near mummies’ spines during burial to ensure stability in the afterlife.

Was Scepter: Power and dominion

The Was scepter (wꜣs) features a long staff with a stylized animal head and a forked bottom end. People first used this ancient egypt vocabulary symbol during the First Dynasty (3150-2613 BCE) to represent power, dominion, control over chaos, and divine authority.

Gods, pharaohs, and priests carried the Was scepter to show their authority and divine connection. The scepter’s meaning changed based on who held it—Isis used it for duality and fertility, Hathor for happiness, Horus for the sky, and Ra for rebirth.

This ancient egyptian words symbol connected the mortal realm with the underworld as a magical tool. Its connection to Set made it a symbol of control over chaos.

Udjat Eye: Healing and protection

The Udjat Eye (Eye of Horus), a famous egypt terms symbol, stood for healing, protection, and restoration. The myth tells how Horus lost his eye fighting Seth, but magic restored it and brought his father Osiris back to life.

This ancient egypt words that start with e (eye) symbol protected against evil, showed royal power, and had mathematical meaning. Each eye part linked to different senses—smell on the right, sight in the pupil, hearing on the left, taste in the curved tail, and touch in the teardrop.

Healers used the Udjat Eye to treat patients, especially for eye problems. People drew the eye on linen or papyrus to create temporary protective amulets during dangerous times like illness or childbirth.

Cartouche: Eternal name of the pharaoh

The cartouche encircles royal names in hieroglyphic writing with an oval shape and a horizontal line at one end. This ancient egypt terminology emerged during the Third Dynasty but became popular under Pharaoh Sneferu at the Fourth Dynasty’s start.

Royal titularies had five parts, but only two went inside cartouches—the prenomen (throne name) and nomen (birth name). The nomen usually included a god’s name, while “Re,” the sun god, always appeared in the prenomen.

Pharaohs exclusively wore cartouches to guard against evil spirits in both life and death. These egyptian words and meanings help archeologists date tombs and their contents. The cartouche later became a general symbol of good luck and evil protection.

Words of Power: Writing and Language in Egypt

Ancient Egyptian language was way beyond the reach and influence of basic communication. Ancient egyptian words possessed magical properties that could change the world through spoken words or written inscriptions. This belief came from Thoth, the god who gave writing to Egyptians. They called their script medu-netjer – “the god’s words”.

Hieroglyphs vs. Hieratic: Two writing systems

Hieroglyphics (meaning “sacred carvings” in Greek) appeared before the Early Dynastic Period (c. 3150-2613 BCE). This complex system mixed ideograms, logograms, and phonograms with over 750 base signs and thousands of variations. Beautiful as they were, hieroglyphs proved impractical for everyday use. A more cursive script called hieratic (“sacred writing”) soon developed.

Hieratic script used simpler versions of hieroglyphic symbols and became the main writing system for administrative documents, business records, and religious texts. Demotic script (“popular writing”) became accessible to more people around 650 BCE and remained in use for another 1,000 years.

Papyrus: More than just paper

The word “paper” comes from papyrus, which changed written communication forever. This writing surface first showed up around 3000 BCE, made from the papyrus plant native to the Nile Delta. Workers sliced the plant’s pith into strips, arranged them in crisscross patterns, pressed them together, and dried them under pressure.

Papyrus meant more than just a writing surface – it symbolized rebirth and creation in Egyptian cosmology. Its light weight and flexibility made it perfect for scrolls, which helped preserve and spread knowledge throughout the ancient world.

Scribes: The elite writers of Egypt

A tiny fraction of ancient Egyptians could read and write. This made scribes valuable members of society. These professionals spent years to become skilled at their craft. They learned hieratic script first before moving on to hieroglyphics. They used distinctive tools: reed pens, palettes with spaces for red and black ink, and limestone practice tablets.

Scribes were essential to Egyptian administration. They worked as accountants, record-keepers, and tax assessors. Their profession opened doors to social advancement – Horemheb’s story proves this point. He started as a scribe and rose to become pharaoh.

Stelae: Public messages carved in stone

Stelae (wedj in Egyptian, meaning “command”) were upright monuments with texts, images, or both. These stone slabs first appeared during the First Dynasty as burial markers at Abydos. They served many purposes: they commemorated people, recorded decrees, marked boundaries, and documented military victories.

Funerary stelae kept the deceased’s identity alive and asked visitors to bring offerings. People placed votive stelae in temples to ask for divine help with healing or wishes. The boundary stelae marked territorial limits, like those that defined Akhetaten’s edges during Akhenaten’s reign.

Burial Practices and Magical Tools

Ancient Egyptians created a complex system of funerary artifacts to help the deceased reach the afterlife. These ancient egypt words show us how they preserved bodies and provided for the soul’s needs.

Canopic Jars: Guardians of the organs

The ancient Egyptians used canopic jars to store and preserve vital organs after mummification. These jars held the lungs, liver, stomach, and intestines. Each jar had a distinctive stopper that represented one of Horus’s four sons. Imsety, with his human head, guarded the liver. Hapy, showing a baboon head, protected the lungs. Duamutef’s jackal head watched over the stomach, and Qebehsenuef’s falcon head safeguarded the intestines. Craftsmen made these vessels from limestone, wood, faience, or clay. Their design changed from the Old Kingdom through the Late Period.

Shabti: Servants for the afterlife

Shabti dolls acted as magical workers in Osiris’s realm. These small figures would respond to work calls on behalf of the dead by saying “I will do it, verily I am here when thou callest”. The ideal tomb contained 365 shabtis—one for each day of the year. Overseer figures with whips supervised groups of ten workers. The number of shabtis showed the dead person’s wealth and status.

Amulets: Hidden meanings in shapes

Amulets protected both living people and the dead. These magical objects lay within mummy wrappings to protect the deceased on their way to the afterlife. The heart scarab stood out as a crucial funerary amulet. People placed it over the heart to stop it from “betraying” its owner during the weighing of the heart ceremony.

Sarcophagus vs. Coffin: What’s the difference?

Egyptians used the term sarcophagus for outer stone containers, while coffins meant wooden cases placed inside. Coffin designs evolved over time. Simple rectangular boxes gave way to anthropoid (human-shaped) forms during the Middle Kingdom. Rich Egyptians often used several nested coffins. King Tutankhamun’s tomb famously held three anthropoid coffins inside a rectangular sarcophagus.

Book of the Dead: A guidebook for the soul

The Book of the Dead, which translates to “Spells of Coming Forth by Day,” helped souls navigate the afterlife. This collection had about 200 spells that taught how to overcome challenges in the underworld. Unlike the Pyramid and Coffin Texts that only royalty could use, the Book of the Dead became accessible to more people who could afford it.

Crowns, Colors, and Ceremonies

Royal regalia and ceremonial objects in ancient Egypt served as powerful visual ancient egypt words that showed authority and cosmic order.

Deshret and Hedjet: Red and white crowns

The Deshret (Red Crown) represented Lower Egypt and the fertile Nile Delta. This distinctive bowl-shaped crown had a curled projection at the front. The cobra goddess Wadjet’s association with the Deshret made it a symbol of protection and rulership. The Hedjet (White Crown) stood for Upper Egypt. This conical white headpiece became southern Egyptian territories’ emblem and linked closely to the vulture goddess Nekhbet. These crowns played a vital role throughout Egyptian history as visual egyptian terms that showed geographical control and divine protection.

Pschent: The double crown of unity

The Pschent merged both Red and White crowns into one powerful ancient egypt vocabulary symbol. Ancient Egyptians called it “Pa-sekhemty” (The Two Powerful Ones). This double crown showed unified rule over Upper and Lower Egypt. While Pharaoh Menes gets credit for it, the earliest proven depiction comes from First Dynasty Pharaoh Djet. The crown carried two divine emblems—Wadjet’s uraeus (cobra) and Nekhbet’s vulture—known together as “The Two Ladies”.

Sed Festival: Proving the pharaoh’s strength

The Sed Festival (Heb-Sed) replaced ritual king-killing and celebrated a pharaoh’s continued successful rule. This ceremony happened after 30 years of reign and every 3-4 years after that to reinforce royal authority. The pharaoh made offerings to gods during this detailed ritual. He wore both Red and White crowns and ran a ceremonial course four times in a short kilt with an animal tail. Priests then carried him to visit chapels of deities from both Upper and Lower Egypt.

Barque: Boats of the gods

Sacred barques helped gods travel between realms. Ra’s solar barque stands out among these ancient egyptian words. The sun god sailed across the sky in the Mandjet (Day-barque) and through the underworld in the Mesektet (Night-barque). Other gods had their own vessels too. Amun’s ship, “Userhetamon” (Mighty of Brow is Amun), gleamed with gold above the waterline and featured cabins, obelisks, and intricate decorations. Osiris’s Neshmet barque moved his statue during Abydos festivals.

Nemes: The striped headcloth of kings

The Nemes headcloth—the most familiar ancient egypt words that start with n—used striped fabric to cover the crown and back of the head. This firm linen headdress had lappets (flaps) that hung behind the ears and shoulders. King Den’s ivory label from the First Dynasty shows its earliest known image. The Nemes usually came in bright colors with blue and gold stripes and framed the pharaoh’s face to show his power. Ramesses II’s statues at Abu Simbel show how it sometimes paired with the double crown.

Summing all up

Ancient Egyptian words exceed basic linguistics and reveal the story of one of history’s most advanced civilizations. This experience shows how Egyptians built a rich vocabulary that captured their deep understanding of life, spirituality, and the afterlife. Their complex view of the soul proves their remarkable wisdom – Ka represented life force, Ba showed mobile personality, and Akh embodied the transformed spirit.

The symbolic language of ancient Egyptians went beyond written words. Each symbol – the Ankh, Djed, Was Scepter, Udjat Eye, and Cartouche – held powerful meanings in their belief system. Their writing systems, hieroglyphics and hieratic script, connected humans with gods. Papyrus changed how people preserved and shared knowledge.

Their burial practices showed their dedication to afterlife preparation. Each item served a specific purpose in the journey to eternal life – from canopic jars and shabti figurines to protective amulets and detailed coffins. The Book of the Dead gave crucial guidance to navigate the underworld’s challenges.

Royal symbols and ceremonies used visual language to reinforce divine authority. The Deshret and Hedjet crowns, along with the unifying Pschent, communicated cosmic order. The rejuvenating Sed Festival and the gods’ sacred barques established legitimacy.

The Egyptian civilization thrived for thousands of years because their language and symbols created a unified worldview linking daily life to eternal existence. Though their civilization faded, their words and symbols still captivate us. They teach us how humans imagine life, death, and what lies beyond.

Here are some FAQs about Ancient Egypt words:

What are some words to describe ancient Egypt?

When exploring ancient egypt vocabulary words, terms like “hieroglyphic,” “pharaonic,” and “Nile-centric” perfectly capture its essence. Other ancient egypt words include “polytheistic,” “monumental,” and “afterlife-focused” to describe their religious and architectural achievements. These descriptors reflect the civilization’s unique characteristics that fascinate historians today.

What is the Egyptian word for power?

In ancient egypt words that start with f, “Ferr” (also spelled “Farr”) represented divine power and authority. Another powerful term among ancient egypt vocabulary words was “Heka,” meaning magical power. These concepts were central to pharaonic rule and the gods’ influence in Egyptian cosmology.

What did the ancient Egyptians speak?

The ancient Egyptians spoke several language stages, with ancient egypt words evolving from Old Egyptian to Coptic over millennia. Their ancient egypt vocabulary words were written in hieroglyphic, hieratic, and demotic scripts. The language belongs to the Afro-Asiatic family, with ancient egypt words that start with e like “Em” (meaning “in”) appearing in early texts.

How do you say beautiful in ancient Egyptian?

The ancient egypt words for beautiful included “Nefer” (nfr), a common term appearing in names like Nefertiti. This important word in ancient egypt vocabulary words symbolized both physical beauty and perfection. Other related terms described specific beautiful qualities in people, art, and the natural world.

What is the Egyptian word for light?

Among significant ancient egypt words that start with e, “Akh” represented the concept of light and radiance. Another key term in ancient egypt vocabulary words was “Ra” (the sun god), embodying sunlight’s divine power. These words held both literal and spiritual meanings in Egyptian cosmology.

What did ancient Egypt call itself?

In ancient egypt words, the civilization referred to its land as “Kemet” (Kmt), meaning “Black Land” after the fertile Nile soil. This foundational term in ancient egypt vocabulary words contrasted with “Deshret,” the Red Land of deserts. Another name was “Ta-Meri” (Beloved Land) among ancient egypt words that start with f (from “Ta-Meri-f”).